Library

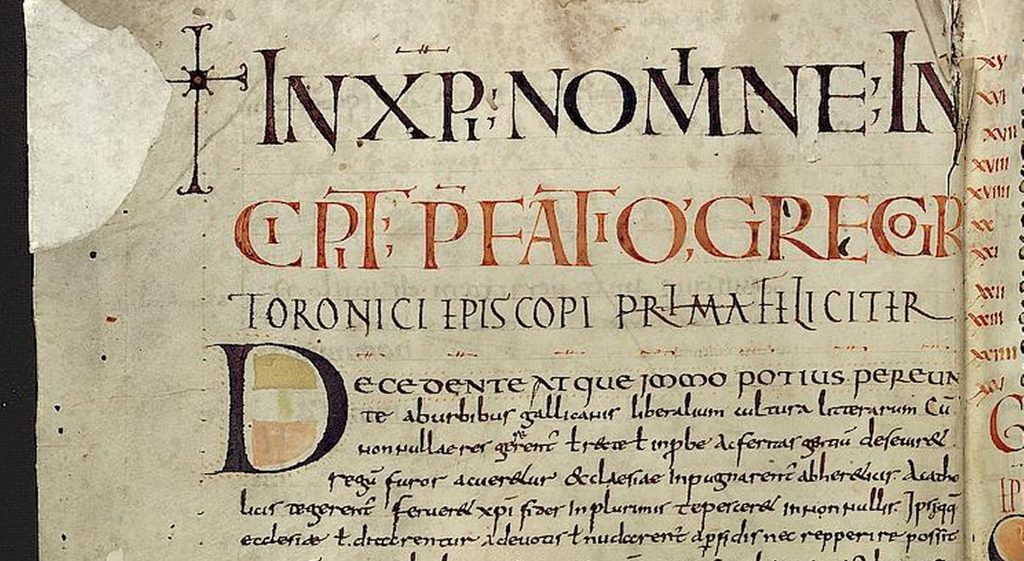

One hundred years after its foundation, the Lorsch Library, with around 500 codices, was already considered one of the most important of the early and high Middle Ages. Charlemagne’s imperial monastery thus also became part of the Carolingians’ educational endeavors. The Lorsch Library was particularly famous for the manuscripts kept here, some of which date back to the 4th century. In addition to biblical texts, the focus was on the writings of the Church Fathers. However, the Lorsch Scriptorium itself also produced valuable and important writings, such as the Lorsch Gospels, the Lorsch Pharmacopoeia and the Lorsch Codex, which is also known today as Germany’s “Grundbuch” (German land register).

As much as it is possible to imagine Lorsch Abbey as a powerful center in a political sense, especially in the first centuries of its history, it is also important to give due consideration to its cultural and intellectual significance.

It is striking that Lorsch, under the direct influence of the court and Metz Cathedral, quickly developed a special feature: an efficient scriptorium, combined with a very well-stocked library. What took decades in other places took just a few years in Lorsch. And it was precisely in the nineties of the 8th century, barely a generation after the abbey was founded, that it can be proven with certainty that Lorsch played a part in the court’s ambitious educational policy plans, a program that became of crucial importance for the paths that the cultural-historical development of the West was to take from then on. The relatively short Carolingian period played a very important role in this; it is the mediating link between antiquity and the Middle Ages. The educational program that was developed at the Court would have remained just a program and theory if some important centers had not implemented these ideas, filled them with content and finally passed them on.

Lorsch was one such center in these decades: The Lorsch Pharmacopoeia responds to the court scholars’ demand to equip future clerics with a basic knowledge of pharmacology, which until then had been regarded as a pagan discipline, with its preface, which can be counted among the key texts of the so-called Carolingian Renaissance; Lorsch responds to the demand to study the pagan classics, above all the poets, in the interest of a deeper penetration into the wisdom and beauty of the Holy Scriptures, with a remarkable reception of the Roman poet prince Virgil. If the contents of the Lorsch Library, of which around three hundred manuscript volumes have survived and which is now scattered across 73 libraries worldwide, had been better researched, more examples could probably be cited.

Lorsch is – and this can be said with a clear conscience at least for the end of the 8th century – a particularly active center for the consolidation of all available knowledge of the time, “networked” with the intellectual elite of the empire through its abbots. We cannot say with the same certainty whether it was also a place where knowledge was imparted – the (at least existing) traces of a monastic school and, strangely enough, the evidence of its own literary productions are too sparse. This makes the almost encyclopaedic collection of the library of St. Nazarius all the more impressive. Many centuries later, in the late phase of the abbey, many scholars came to Lorsch: scholarly professors from Heidelberg University, humanists searching for classical texts in the 15. and 16th century. One can understand the interest of Elector Ottheinrich in immediately securing the remaining library on the occasion of the dissolution of the monastery (probably in 1556/1557) and incorporating it into his court library and university library, the famous “Palatina”.

Dr. Hermann Schefers